Explainer – The government has announced the country is moving to phase three – but what does that mean? RNZ is here to clear it all up.

Covid-19 Response Minister Chris Hipkins and Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield this afternoon announced New Zealand would move to phase three from midnight tonight, the final phase of the government’s Omicron response.

Health workers and testing labs have been under increasing pressure as the outbreak grows, and have been hoping for a swift shift to the next phase of the government’s plan.

But what is phase three? Why does it seem to be lowering requirements just when the outbreak is growing? And when will it all end? RNZ is here to clear it all up.

What is phase three?

Phase three is designed to help the health system handle an Omicron outbreak of several thousand new cases a day.

The shift means a greater focus on individual responsibility, rather than relying on health services to be able to cope and contact trace in the way they had earlier in the pandemic.

“Act as if you might have Covid, and behave accordingly to protect others including using masks and so on,” Dr Bloomfield has advised.

Testing

Rapid antigen (RAT) tests will be considered enough to diagnose symptomatic people and priority groups. This means people will not need to follow up a positive RAT test with a PCR test to be considered a confirmed case.

The advice to get a test if you have symptoms still holds – but people will shift to getting a RAT instead of PCR. Supervised RATs will be available at clinics from today, with locations listed on the Healthpoint website.

These tests, which are self-administered and give results in 15 minutes, should be available for free from doctors, pharmacies, community testing centres or workplaces for those who need them. They are also expected to be available for a price in retail settings from March.

Critical workers including those in healthcare can use these tests daily to be able to go to work even if they are a close contact, so long as their employer is signed up to the scheme.

Household contacts should get a test on day three and day 10 of their isolation period. Contacts not living in the same house should get a test on day five or if symptoms appear.

PCR testing will continue to be used for those who need it.

Case and contact management

People testing positive are notified by text message, not a phone call, and will be sent a link to complete an online contact tracing form to identify contacts and support needs. There will be a phone call option available for those without internet access.

People who do not respond to the text will be followed up to check whether they need additional health or social supports.

Contacts may be automatically notified from the contact tracing form, but cases should also notify their close contacts themselves.

The definition of ‘contact’ changes to mean household and household-like contacts only. Contacts will only be required to isolate if they are high-risk (household) contacts.

Notification of locations of interest are restricted to the most high-risk events and settings, such as hospitals and aged care.

Isolation

Most people who test positive will be expected to look after themselves at home, leaving clinical care available for those with greater need.

With this in mind, people are advised to prepare for self-isolation by getting an isolation pack together, and speaking to friends and whānau about how they would manage.

Isolation times are similar to the shorter period introduced in phase two: 10 days for cases and household contacts.

Asymptomatic household contacts who return two negative tests will be able to leave isolation after 10 days, regardless of whether another member of their household tests positive.

While only people who are a case confirmed by a PCR or rapid antigen test – and those in their household – are legally required to isolate, others may do so if it is convenient, to reduce the risk of spreading the virus further. Other steps like avoiding visiting people in aged care or those who have immune deficiencies is also advised.

Non-household contacts are asked to monitor for symptoms

Official messaging is that there is unlikely to be other accommodation – such as MIQ – available for most cases. However, the government has repeatedly said arrangements will be made for those who have no home, are living in a vehicle, or are in other difficult circumstances.

Why do we need it?

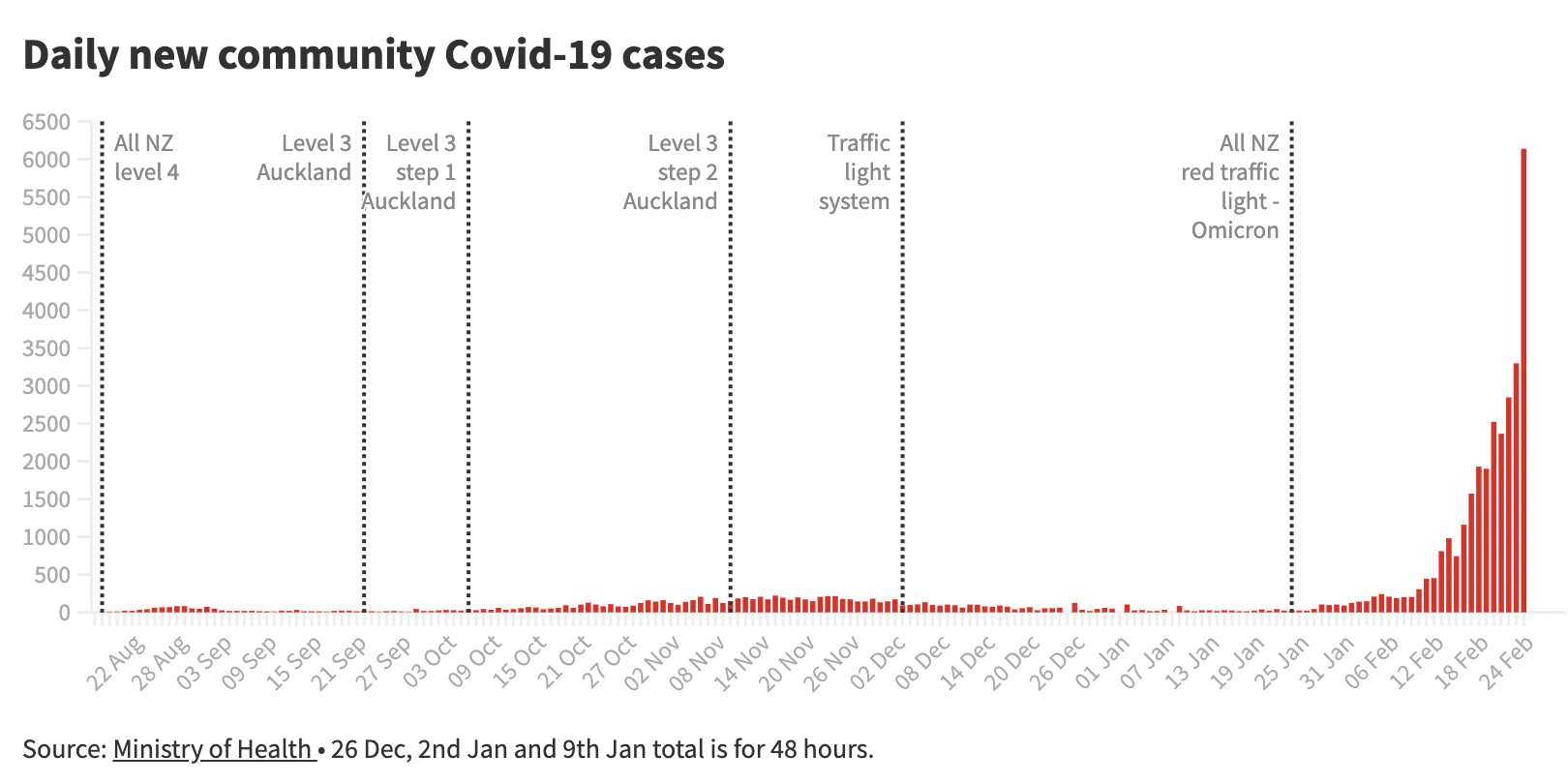

While Omicron is considered milder than the dangerous Delta variant and is less likely to put people in hospital, some people do still get very sick and it spreads so quickly many more people can be expected to get very ill.

That is, while any one person is less likely to get severe symptoms, many more people overall can be quickly expected to get the virus, so the total number of people who do end up in hospital all at once is likely to be significant.

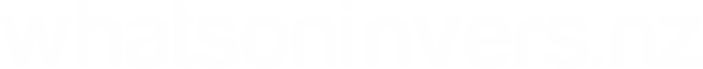

New Zealand has been recording steadily increasing numbers of daily cases, topping 3000 yesterday and hovering around 5000 today – the trigger for moving to phase three.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has this week been saying the outbreak is not expected to peak for three to six weeks, and the nature of Omicron means case numbers can be expected to keep doubling every three to five days until we near that peak.

New modelling shows the peak of Covid-19 in the Omicron outbreak in Auckland and Northland alone could reach 4000 daily cases, if transmission is low, or 9000 if it is not.

Even a low-transmission scenario would mean about 400 cases from Auckland and Northland in hospitals at any given time. It would put heavy strain on New Zealand’s health system – general wards as well as intensive care – which has suffered decades of underinvestment from successive governments.

Bloomfield noted today that the low-transmission scenario relies on widespread uptake of the booster shot.

The high number of cases from Omicron means the follow-up interviews with cases and high-intensity contact tracing systems will not be able to keep up, so the systems will instead focus on the most high-risk people.

During this time, New Zealand can also be expected to remain in the red traffic light setting. Ardern has suggested these settings, the vaccine passes and mandates are likely to last until the country has progressed well past the peak of cases, so the health system remains operational.

Vaccinations – especially booster doses – are a big help in reducing hospitalisation from Omicron, and New Zealand’s high rates will have helped prevent some of the high death rates seen overseas.

Bloomfield also noted studies from the US have shown vaccines – particularly the booster shot – do still help reduce the spread of Omicron.

“One of the studies, which was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, shows that compared with being unvaccinated the odds of contracting Omicron after receiving three doses dropped by 67 percent – two thirds – and for Delta the risk declined by a stunning 93 percent.”

Masks and other public health measures like frequent, thorough hand-washing also help slow the spread of the virus, so it will be important for people to continue to do this while the virus is spreading.

While the government says it intends for heavy lockdowns to be a thing of the past, the traffic light system does maintain localised lockdowns as an option should things get really out of control.

Meanwhile, the government is also gearing up for more people to start isolating at home when arriving from overseas, beginning from next week with those coming from Australia and expanding to New Zealanders coming from the rest of the world two weeks later.

Hipkins said further advice on whether arrivals will continue to be required to isolate is being sought, considering the virus is circulating widely already.

Source: rnz.co.nz Republished by arrangement.